ETA is one of the most prevalent and powerful companies in the modern watch industry. It is Switzerland’s largest movement maker with countless small and major brands relying on the products they make. Its story has, as we will learn, defined the watch industry of today. However, despite all its previous and present roles in horology, for many, ETA remains a relatively unknown manufacture, or worse: a three-letter word that scarcely means more than the fact that the movement inside their watch was not made by the company whose name is on the dial.

One of the reasons for this can be found in the marketing practices of the industry. We see retail brands tirelessly looking for yet another way of exploiting their history so as to convince the pondering buyer. ETA however, unlike retail brands, does not want to sell directly to the public. Consequently, they will never publicly advertise their technical achievements to make you or I buy a movement or two from them. What they do instead is sell ébauches (semi-assembled movements) and complete movements in vast quantities to watch brands, who will then dress them up in accordance with their own brand’s DNA.

The other reason why it might be difficult for the masses to learn more about the manufacture is that in-house movements have become a major selling point for most mid- to high-end brands. Therefore, when it comes to a watch without a proprietary movement, the general method is to rename the ETA (or any other supplied) movement to a different code chosen by the brand. Surely, sometimes the base ETA/Sellita/Soprod, etc. movement is modified by the company that purchased it, but oftentimes the only thing “custom” about one of these calibers is the rotor with the particular brand’s name on it.

As a result, for those relatively unfamiliar with the world of watch making, ETA might appear as if it was some sort of an objectionable, undesirable name in the industry, something that should be avoided. But that could not be further from the truth. ETA is an indispensable element and something without which Swiss watch making would never be what it is today. In this article we will discuss the history of ETA through reliving the incredible ups and downs of not just a manufacture, but an entire industry as well.

Before we get into the details, please allow me to note that there is no one complete source of information, no one place where all relevant data is easily available. At times, controversial data can be found, primarily because getting exact statistics regarding the earlier years is very difficult. Having said that, we will closely follow the history of the Swiss watch making industry to see how ETA not only managed to fit into it, but also how it made a major difference just when it was most sorely needed. We begin with looking at the watch industry of the early 1900s to see where and how it all began for the company.

Prologue

By the early 20th century, the Swiss watch industry was comprised of larger manufactures (etablisseurs) which were assembling complete watches mostly from purchased parts and movement kits and workshops (ateliers) which specialized in either making different parts or building ébauches. In practice, this meant that a number of ateliers were making very specific components (such as the balance spring, mainspring and other parts that demanded great precision and expertise) while other workshops were building semi-assembled watch movements (ébauches). Ébauches are movements that contain most basic structural elements but are not equipped with a mainspring or the escapement. You might rightfully ask, “If everyone had been making parts and unfinished movements, then who built watches?” The answer is that the blank movements, as well as all other components, were sold by these independent workshops to watch assembling firms (etablisseurs) who then modified, decorated, fully assembled and regulated them for their own timepieces. However…

The beginning of World War I turned the industry inside out as most supplier firms quit making watches or other components and started using their machines and human resources to produce and sell ammunition. Since demand had been much greater for ammo than for fine watches, this was a rather obvious decision. Once the war was over though there was no need for such immense amounts of bullets and all these firms wanted to return to their normal activity to make ébauches and components again. And so they did, causing a sudden oversupply of their products. They all acted independently of one another as there were no powerful groups or authorities to control them. Consequently, it was much too late when they realized that the demand from watch making companies for such a vast amount of parts or ébauches was greatly insufficient.

The workshops were desperate to stay alive and to achieve that they had to get rid of their piled up stocks – at any price. In a vicious pricing competition, they sold all redundant parts to Swiss companies and – to make things worse – to non-Swiss competitor watchmakers as well! These (mainly American) companies bought these high quality Swiss movements and used them in their lower priced watches. This way they could provide much more reasonably priced timepieces than their Swiss counterparts while using just about the same movements! In essence, Swiss workshops were selling components at great losses when the companies who they wanted to buy from them were going under because non-Swiss brands were selling comparable watches at much lower prices.

These seriously daunting circumstances were topped off with heedless crediting by some of the Swiss banks. In summary, the industry had to face steeply decreasing turnover, strong foreigner competition gaining momentum, and an unremittingly increasing debt. The result? By the mid 1920s the industry owed about 200 million Swiss francs to its lenders.

The Gears Line Up for Partnership

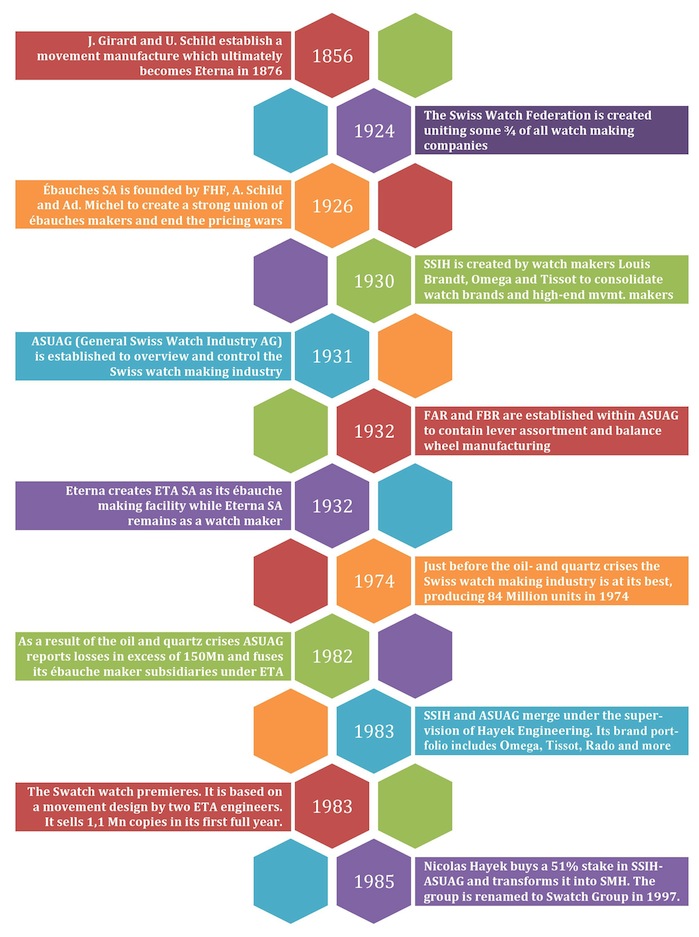

It was obvious that strong corrective measures were necessary as the companies themselves, separately, never had the power to make a difference and to turn things around. The first step in an effort to break these unnerving trends was the 1924 founding of the Swiss Watch Federation (FH, for short), uniting some three quarters of the industry. Two years later, as a second stage, with strong financial support from some powerful Swiss banks, the corporate trust Ébauches SA was created by the three largest movement makers – Schild SA (ASSA), Fabrique d’horlogerie de Fontainemelon (FHF), and A. Michel SA (AM).

The three basic rules that these companies set for themselves made this a unique co-operation and one of great importance. First, all three founders maintained the right to run their management as they deemed best while they agreed on setting the same prices. This removed the threat of competing against each other by cutting prices to dangerous levels. Secondly, they standardized the specifications of some of the movement parts to optimize manufacturing and lower the related costs. Finally, in December of 1928, they strongly regulated the export of unassembled movement parts (chablons) with the “convention de chablonnage” in an attempt to eliminate the threat of any of the participants selling components to foreigner companies. This did sound very promising and so by the early 1930s more than 90% of all ébauche-makers had joined this holding.

As most ébauche workshops have gathered under the virtual roof of Ébauches SA, the companies assembling and selling complete watches saw the benefits of such a move as well and so they began looking for a way to join their forces. Soon enough, in 1930, the group SSIH was established by the merger of the houses Louis Brandt, Omega and Tissot. In 1932 they were accompanied by Lemania, now enabling the group to create chronographs.

Despite all the clever co-operations between the Swiss companies, they had no chance to avoid the next crisis coming their way. Closely following the internal pricing issues of the 1920s is the financial crisis stemming from 1929. The Great Depression, of course, hindered the entire industry causing some 20,000 watch makers to lose their jobs. While uniting the majority of movement makers under Ébauches SA had been an important step, the extended managerial freedom meant that the corporate trust lost its abilities of defining a singular direction which participants could follow collectively. There was an obvious need for another organization, one with the power to overview and regulate Swiss movement making as a whole. Consequently, in 1931, the General Swiss Watch Industry AG (ASUAG) was established. It was partially funded by the Swiss Confederation with a hefty sum of 13,5 Million francs (out of the total 50 Million franc budget that was required to create ASUAG). All that money was to serve one clear intention: to create a super holding that would amalgamate and subsequently direct the industry. With its massive financial backing, ASUAG advanced accordingly. By 1932 it united several manufacturers of movement parts under its subsidiaries of FAR and FBR, responsible for lever assortments and balance wheels, respectively.

Dr. Joseph Girard and the 28-year old school teacher Urs Schild founded the ébauche factory “Dr. Girard & Schild“, the company that was renamed to Eterna in 1905

The Beginning of ETA

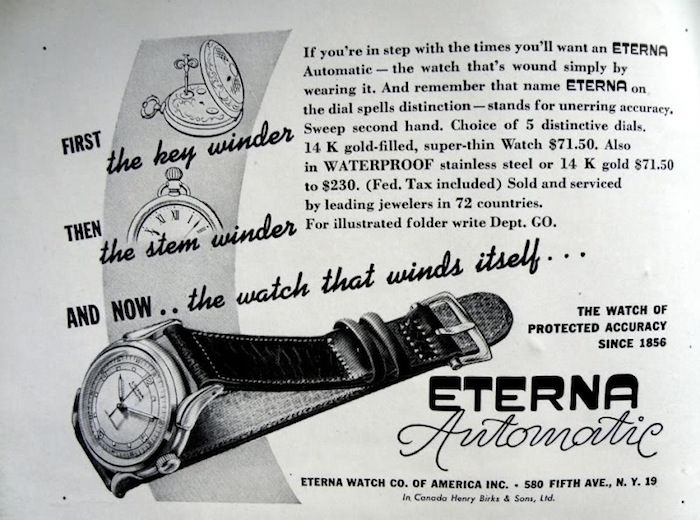

Missing from the participants of any of these giants was Eterna – and with this we really are getting closer to understanding how ETA SA came to be as we presently know it. Eterna was originally founded as the ébauche factory “Dr. Girard & Schild” in 1856 and was renamed to Eterna later on, in 1905. Regardless of the name changes and one heir following the other in leading the company, by the crisis of 1929, Eterna had already employed more than 800 people and produced about two million parts annually.

At the time, the firm had been managed by Theodor Schild, the founder’s son. He felt great responsibility for the company his father had created, but he also had to see that Eterna was affected by the economical meltdown no less than any other company around it. Theodor saw the possible advantages the merger with ASUAG/Ébauches SA could bring in such a problematic situation, but he remained reluctant to actually join them. First of all, he wanted to make sure that his firm’s freedom in decision-making remained intact after they united. Secondly, Ébauches SA – as its name suggests – was exclusively for ébauche-makers and not for watch assemblers. This meant that Eterna had to be split into two parts: one to join the holding and one to manufacture complete watches. Once he eventually came to an agreement with the super holdings, the company was split into two indeed. Eterna remained a company assembling watches while it created its new movement maker division that was called ETA SA.

As we can see, ETA could never have come to existence had it not been for the countless ups and downs of the industry and all the crises that needed urgent solutions. And despite the relatively “recent” date of 1932, when ETA was officially established, we have to note that the manufacture had been making ébauches and movements as “Dr. Girard & Schild” and then as Eterna since 1856. It is just that legally, this movement-maker facility was separated from the mother company of Eterna in 1932 and started its new life as ETA SA. Once the merger was completed, Theodor Schild retired and Rudolf Schild took the helm of ETA.

The complex tasks of movement manufacturing had been split up into three large segments within ASUAG. Manufactures like FHF, Fleurier, Unitas and others were responsible for building hand-wound movements, chronographs were created by Valjoux and Venus, while ETA and some others were in the business of building automatic ones – something fairly new on the market. By 1948 ETA established its watch making school that allowed it to recruit and train craftsmen as the industry rapidly expanded during the ‘50s and early ‘60s. Furthermore, ETA had been busy developing new movements that incorporated ball-bearings in the automatic winding mechanism.

In 1948, their efforts came to fruition as they announced the Eterna-matic, the first automatic wristwatch with this innovation. This new technology proved to be so successful that a formation of five ball bearings have made up the logo of Eterna ever since. Finally, they also tested high-frequency movements and in the mid-seventies even managed to break into what would later mostly remain Zenith-territory: 36,000 vibrations per hour. Unfortunately, these models were discontinued for some startling reasons, reasons which we are just about to discover.

Rounding out the list of crises are not one, but two major downturns actually. Both stemming from the middle of the 1970s. At the time, in 1974 to be exact, the industry was at its best, producing about 84 million watches a year! Clearly, the oil- and quartz- crises could not have come at a worse time or be any more painful of a hit for the Swiss. In a nutshell, the primary issue was with relative value as, Swiss watches became horrendously expensive as a cumulative result of these two crises… more »