Frankly, I unashamedly took every opportunity on every single day to wear the Richard Mille RM 011 Felipe Massa Black Night NTPT Carbon watch while reviewing it over these past couple of weeks – much as how one would spend every last moment driving that (thus far imaginary) convertible supercar parked in front of the house if finally given the chance… The irresistible force of sheer curiosity and excitement will not allow you to do anything else but make use of such fascinating circumstances. But what is all the fuss about?

These couple of weeks have, finally, allowed me to get a better idea about what it is like to live with a $140,000-plus Richard Mille on the wrist, and to see if it was as remarkable an experience as I anticipated. Ups and downs, and all there is to know about it, let’s find out!

Because Richard Mille watches are notoriously expensive, fairly complicated, and also tend to feature some new, high-tech material, they make for a difficult review subject. There are numerous factors for us to consider – including those that will help us answer why Richard Mille’s watches demand the prices they do, and why they can keep on producing over 4,000 of them per year.

So, first, let us put the concept into context – you know, that mind-boggling idea of a six – figure – priced – annual – calendar – chronograph – in – a – non – precious – metal – case.

Since the dawn of the new millennium, Richard Mille has been the, and I mean the ultra-expensive, extremely successful avant-garde watch brand in the watch industry – that is just a fact. However, for anyone without oligarch predecessors or direct access to an oil refinery’s yearly turnover, comprehending prices Richard Mille watches demand will likely prove to be extremely difficult.

So that we can compare, here are the very basics of a normal luxury brand’s normal pricing procedure: generally, a company first determines its specific market segment, its target audience, as well as the respective price point these factors necessitate. Only after all this has been taken into account does it start to develop and finalize the product itself. Needless to say, this method levies restrictions on the product itself, as it will ultimately have to comply with these predetermined cost- and pricing-related requirements.

As Richard Mille himself explained, the process of pricing his watches (and hence his brand) is unlike most other pricing strategies in the sense that what they do is first come up with an idea for a product, then they develop that idea so that the final product comes in as close as possible to what he and his team had dreamt it up to be. And only once all this has been achieved and the cost of all these efforts are taken into consideration do they set the final price.

Sounds very luxurious, but what brands say and they actually deliver are often two different things – so let’s see how (or if at all) this turns into reality.

Sure, the lack of such cost-related limitations on Richard Mille watches becomes immediately apparent when you glance at their price tags; which can make some supercars suddenly appear to be low-budget alternatives in comparison. However, things stay in line with this approach when you take a closer look at the product itself, as well as where and how they are made. So let’s first concentrate on that latter thing, the origins first – very briefly, as we already have a more in-depth article on this topic from the time I visited Richard Mille’s manufactures in Switzerland.

As is the case with most modern, outrageously complicated and super expensive watch brands (of which there actually are more than a few these days), there is no one single facility where all manufacturing processes are simultaneously performed. The reason for this is that there is no one place where, under the same roof, they could simultaneously make watch cases out of unobtainium, machine hundreds of different kinds of delicate movement components, manufacture complex handsets and dials, and then assemble all of these parts into one watch. Watches like the $1,050,000 RM50-02 don’t fall out of the sky, after all – instead, there are numerous specialized suppliers and facilities to be involved.

Richard Mille works with Vaucher Manufacture (read our visit article here) on the relatively more simple movements like ultra-thin calibers, annual calendar chronographs, and such; and with Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi on mind-alteringly complicated movements with novel complications. For cases and some other components, they largely rely on their own, just a few years old, state-of-the-art case-manufacturing facility called ProArt in Les Breuleux, while final assembly of watches primarily happens a few minutes’ drive away from ProArt, at the Richard Mille headquarters.

One of the key take-away messages from my visits to these places was their immediately and universally apparent “anything is possible” approach. Anywhere I looked I saw energetic (oftentimes very young) engineers programming brand new machines and working on novel materials and high-tech composites (such as NTPT carbon, the material used for the case of the subject of this review, but more on that further down). In other departments, they were working on re-assembling super-complicated movements with what appeared to be perfectly calculated movements. All this made things appear so easy that I had to remind myself how they were not milling simple steel cases or servicing base ETA calibers. They made it look easy, but the engineering challenges and the novel nature of these products ensure that these people’s job is to tirelessly keep pushing the envelope – that is what they are paid for, and that is largely what keeps this brand alive.

All this is nice and well, but you might feel it still is not enough to explain how can a brand sell over 3,000 pieces per year – with near-six-figure average prices.

To discover the missing puzzle piece, I’ll ask you to briefly put up with a banality as I try to make my point: there are people, many people, out there in the world who can and indeed are willing to pay virtually any amount of money for what they like and can appreciate. The real question is not whether there are enough of these people out there – because there are – but how a modern brand can connect with them and convince them about its particular products being worth so much?

The real concern for these people is not wasting X or 100X amounts of money on something, but rather being humiliated among their peers by paying for something that had not lived up to their expectations. Something that in a short amount of time turns out to be inferior when compared to products of other competing brands. Their cars, boats, helicopters, etc., all have to be the fastest, and if they have paid the price only for it to not deliver as expected, the brand that failed can soon close shop. There were a few brands that failed to continue to push their design and engineering envelope – and they are nowhere to be seen today. So, the real challenge for Richard Mille is to always keep pushing their limits by using new materials, constantly improving their designs and, in short, to never cease to amaze their clientele.

In the parallel universe of stratospherically priced, remarkably engineered hypercars, car manufacturer McLaren got that mixture perfectly right – and, given their extremely similar positions and techniques, for some time now, I have considered Richard Mille to be the McLaren of watch brands. McLaren, who actually has only recently started to manufacture its own line of road cars, had to overcome car industry giants the same way as Richard Mille did and does in the watch industry – and their recipe for success is the same.

What helps both of these companies cater so effectively to the aforementioned customers is their extremely limited number of instantly recognizable designs, which they constantly refine and upgrade with the latest technologies. This allows them to offer bold new options to those uber-rich who at this point are utterly bored by the idea of getting yet another boring thing from one of the big names but instead are in search of the ultimate toy. They want it to be the lightest, fastest, and yes, the most expensive – and they want it to be instantly recognizable, at least within their own circles.

This is the recipe that they have to follow: no tens of different Richard Mille or McLaren designs, but only one trademark look for either, which, in turn, are tirelessly updated and refined with the latest technologies.

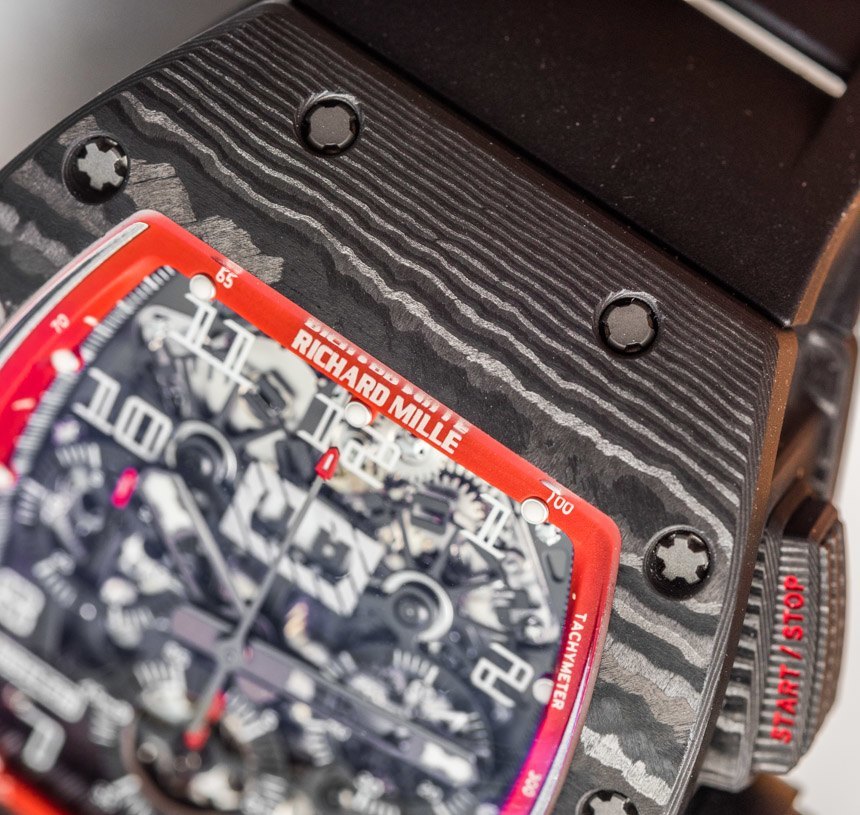

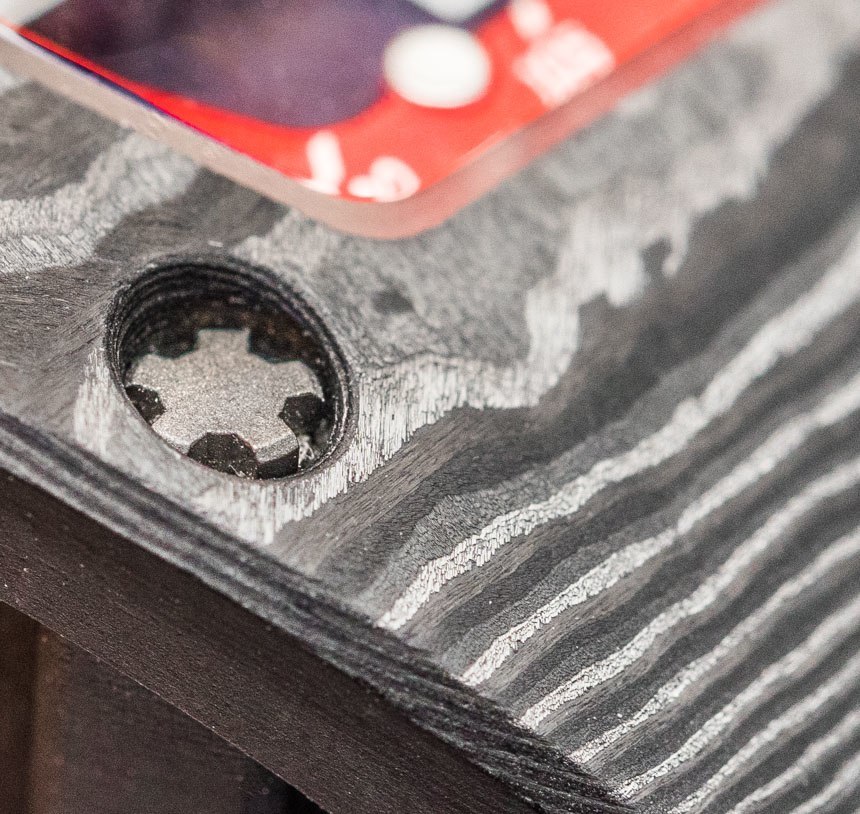

With that (not-so-) brief introduction to its origins in mind, let’s see how all that translates into the subject of this review: the Richard Mille RM 011 Felipe Massa Black Night NTPT watch. The RM 011 is without a shadow of a doubt the most recognizable and successful model Richard Mille has produced thus far. Its tonneau-shaped case with its lugless design, twelve pieces of 5-node screws in the bezel, plus the curved sides and the also noticeably arched case profile… this package is the Richard Mille look.

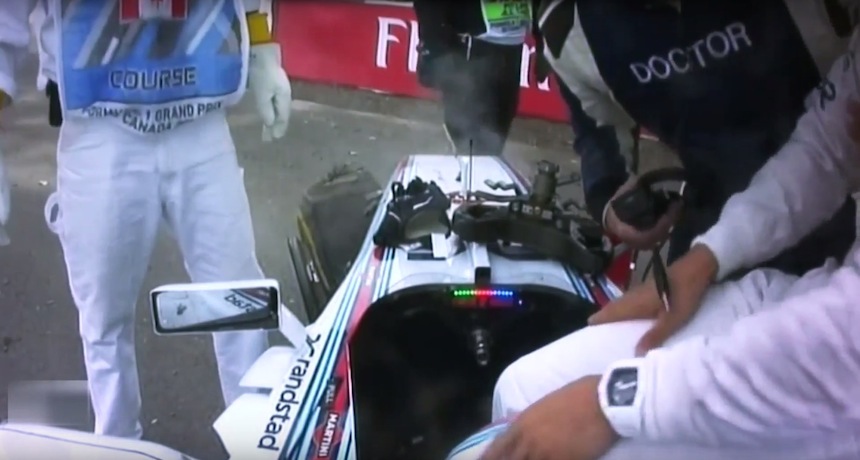

Brazilian Formula-1 driver Felipe Massa has been a friend of the brand for well over ten years, and his name has been part of every RM 011 model ever made. He even wears a Richard Mille watch on his wrist while racing – just see the shot above where he was getting out of a wreck after an unlucky racing incident at the Canadian gran prix a few years ago. It is here where we’ll say that starting with this 2016 season and going on for at least 10 years, Richard Mille is in official partnership with the McLaren Formula-1 racing team.

Obsessive levels of cleanliness and order, mixed with craftsmen and high-tech machines: the most notable similarities between Richard Mille’s case manufacture and McLaren’s Woking facilities.

Now, although as a fan of Formula 1 I admire Massa’s famous sportsmanship and driving skills, I was happy to find that this particular version of the RM 011 does not have his name spelled out in full on the dial, but only honors him in a barely noticeable way, by placing his initials in the model number, displayed right below the 8 o’clock index. While certainly not everyone will share this sentiment, I personally prefer to only see the watchmaker/brand’s name on the dial, and nobody else’s.

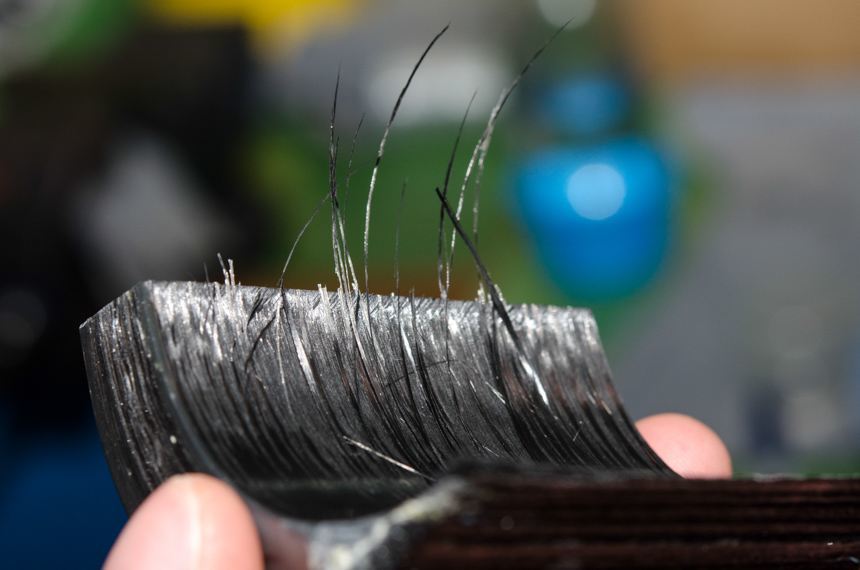

The more fascinating part of the name, though, is the “NTPT” bit, as it refers to the special material the case of the Richard Mille RM 011 Felipe Massa Black Night NTPT is made of. Upon visiting RM’s so-called ProArt case manufacture, I could see for myself how this unusual material ultimately takes shape as one of Richard Mille’s tonneau cases. The base material has been developed by the company that runs under the same name, NTPT, to be used for the masts of racing sailing boats – so it should come as no surprise that the material is extremely rigid and yet also very light.

This is in large part due to its layered construction that comprises hundreds of layers of carbon fiber held in one solid piece, thanks to some epoxy resin and a few turns in ovens that exposed the base material to some hell-on-Earth-like temperatures. But will you use your Richard Mille to fix the mast on your sailing boat? Possibly not, so we shall see what this material actually feels like when used not for parts of a boat, but for an ultra-expensive timepiece.

What first stands out even for the untrained eye is the highly unusual surface. As the milling machine cuts through the hundreds of barely visible layers of the case, the material – thanks to the angle at which the machine cuts it – reveals some fascinating and in all instances unique patterns, strongly reminiscent of those seen on wood surfaces. To the touch, NTPT feels warm and, while under strong magnification (like in the image just above), you can see the tiny fibers of its carbon base. It is always perfectly smooth.

In essence, then, this S-Class AMG Mercedes-priced watch uses high-tech material designed for boat racing – sounds cool, but not imminently luxurious. Upon a closer look, though, we start to scratch the surface – only figuratively, of course, as carbon fiber cases put up with pretty much any abuse extremely well – of just how much effort has gone into making a sports watch into a timepiece that can (and does) sell for six-figure prices.